Sophie Dibben speaks to Louise Walsh, the Cork-born artist, who was thrust into the political melting pot of Belfast aged just 25, with her sculpture, ‘The Monument to the Unknown Woman Worker’.

It’s 1989 and Louise Walsh lives in a grotty flat in Belfast. She’s fresh out of university and just beginning to pursue a career as an artist. A small urban park is opening nearby and Belfast’s City Council invites four professional sculptors into a competition to erect a statue on Great Victoria Street, behind the Crown Bar, a renowned Belfast boozer. The council’s brief invites Louise to model a figurative piece based on a drawing of two women.

Looking back on it now, Walsh recalls the drawing as being “provocative, in a seaside postcard style…[the women] were cartoony, busty.” It showed one looking expectantly for clients, while another looked at a dog peeing against a tree. For Walsh, the image portrayed sex workers in a degrading way.

Where many Northern Irish men were used as ‘cannon fodder’ for war in the 20th century, young women were often just ‘fodder’ – not getting paid while working rotten jobs, offering little pay and no maternity, holidays or sick leave. Sometimes, the alternative option of becoming a sex worker could offer a more viable way to survive, yet Walsh had been given a brief that demonised young women who found themselves taking that route to financially survive.

Not only did it demonise these women, the brief reflected the social history of the area only in terms of its red light district, the Crown Bar historically being a brothel. But, as Walsh points out, this was just one feature of the area, which had a rich social history: it was densely populated, there were linen factories, and all sorts of other livelihoods and professions going on in the community besides sex work.

Walsh began to think long and hard about the authentic female experience in Belfast, also realising that at this point in Northern Ireland the only depiction of the female in sculpture was Queen Victoria. Meanwhile, all the men depicted were “famous for military action, oppressing people or religious dominance,” Walsh recalls.

Playing on the famous idea of the “Monument to the Unknown Soldier” – another way that men are commemorated for giving their lives to war – Walsh conceived of her own version, celebrating unknown woman workers, and pointing out how female sacrifice and service was not elevated like the male. The “Monument to an Unknown Woman worker” was born. Where the ‘Unknown Soldier’ commemorates the working-class man who died fighting for their country, Walsh’s idea would commemorate the countless unknown women who had shaped Belfast.

Speaking about it now, she says, “I knew I had to ‘tip-toe’ around the idea of making a ‘sex worker’ sculpture and making a political point.” So she decided to depict two women, who “you can see as sex workers if you like” because ultimately their low pay or unpaid work prostituted themselves anyway working for little or nothing.

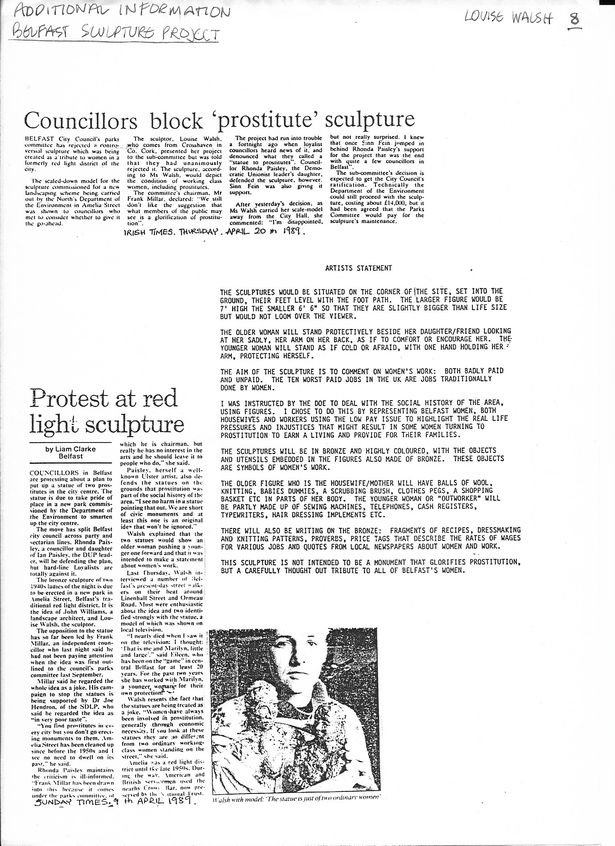

The “Monument to the Unknown Woman worker” commemorates the economy of women with references to typical female jobs. There is an older woman, who works in the home, has a milk bottle on her breast, dummies for earrings, and a colander on her stomach. She is “protective of the younger woman” who holds the lowest-paid jobs and wears a waitressing apron, with a telephone on her elbow, a keyboard on her stomach, and hairdressing scissors in her hair. Also engraved into the sculpture are some inscriptions from 1940’s newspapers such as “she’s engaged” and “doesn’t she look lovely!” to ironise typical media references to women.

Walsh won the competition, and an Independent, right-wing Unionist politician was brought to see the model of the proposed sculpture.

“The proverbial hit the fan.”

The politician went on the news to express his disgust at Walsh’s monument, even though it had already been approved by the competition’s adjudicators and was in fact more moderate than the caricature the brief asked for. But ordinary women were seen as unworthy subjects, and only if their likeness was decorative or sexualised could the sculpture be worth it.

The political manoeuvring began to ban the sculpture. Walsh believes that this was fuelled by the sectarian politics of the time, which pushed ideas about “who gets commemorated” and “who is worthwhile” in Northern Ireland.

There was also an election approaching, likely spurring the politician to draw attention to himself as a decent, upstanding citizen, who would not allow anyone to humiliate Belfast’s public space. Speaking about it, he said, “I heard they are a monument to prostitution….I was told they had breasts but I didn’t have my glasses, so I couldn’t be sure.”

“Belfast has no heart for tarts,” read one headline. “Shady ladies get the boot,” read another. “Protest at the red light sculpture,” a third.

In her rented studio, Walsh was thrown into the deep end of journalist turmoil and kept muttering under her breath “I should just tell everyone the truth.” Her sculpture wasn’t necessarily about sex workers, but this was the sensationalist selling point for the press. The dominant narrative became Walsh making a “dodgy piece about sex work,” instead of anyone questioning, “the notion of what art is, and the notion of commemoration – or the putting up of statues to celebrate a figure who was a decent, upstanding person who deserved to be elevated.”

The argument wore on. In fact, the “Monument to an Unknown Woman Worker” spurred the longest ever debate in the Belfast City Council. “This just shows how much they didn’t talk!” Walsh laughs.

Eventually, the council opposed the project and facilitated the banning of the monument because it was on public land. In 1992, however, a private developer recommissioned the sculpture and it was erected on technically private land outside of Great Victoria Train station. There it still stands, despite also remaining banned from Belfast public land to this day.